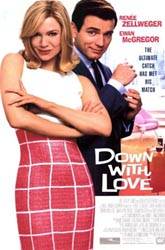

Director: Starring: Release: 14 Feb. 03

|

All the Real Girls BY: DAVID PERRY [NOTE: Since this is more an analysis than a review of All the Real Girls, major plot points including the ending are given away. It is recommended that this only be read after watching the film.] All the Real Girls, David Gordon Green’s slow, lethargic, and amazingly beautiful follow-up to his similarly adjectival first film, George Washington, is the kind of cynical love story you expect from a gaunt 28-year-old. It features people falling into love and falling out of love, but not with the same kind of melodramatics akin to most downbeat love stories. This time the artifice has been removed, and all those awkward pangs of love emphasize what is, unequivocally, a star-crossed affair. Hailing from Arkansas and having attended college in North Carolina, Green has in these two films established himself as the most truthful and articulate directors of the modern southern milieu. His grasp of the desolate feeling of rural southern youth comes from a heart empathizing with those kids you recognize will probably never leave their lower Middle American homes. George Washington, following the collective reaction to the accidental death of one of these kids, seemed to come straight from the grave of William Faulkner or James Agee, methodically looking at what it is to be human and to be southern. All the Real Girls comes from the same level of harrowed empathy, though its grasp of such lofty comparisons to Faulkner or Agee isn’t quite at the same level as the previous film. Sans the abstraction of George Washington but retaining the poetic lyricism, it is more structured, more accessible. While Green is certainly not a film director who covets being called populist, his latest work comes with the approach of a humanist hoping to dash his own cynicism, but ultimately underlining it. The way he covers the ground created by himself and his college friend Paul Schneider is one of reproachful dedication. By turning his attention to something that, evidently, bewilders and beguiles him, Green is much more focused on the narrative and finds the most manageable way to tell the story without coming off as too artsy or pretentious. The central characters, Paul (Schneider) and Noel (Deschanel), seem to be proxy emblems for what Green either saw or felt in his own lifetime. Paul is the person stuck in his North Carolina textile town, attempting to hide his destitute future as a glutton of beer and sex. His friends equally lack ambition, with varying degrees of recognition of such. Noel, on the other hand, has been outside, spending much of her teenage years at an all-girl boarding school. Upon graduation, she returns to her childhood home with the emotional baggage of her arrested development. While she is much more mature than those who have never left the town, she isn’t quite adept at her own possibilities outside of this place. Or, maybe, she’s the smartest of them all, having seen the outside and returned, recognizing the underlying beauty of it (captured by Tim Orr’s breathtaking cinematography). Alfred Lord Tennyson famously said “’Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all,” which seems to be the central thesis behind Green’s drama as he uncomfortably shows the relationship between those caught in a void of southern rustics and those caught in the similarly inescapable void of lost love. Paul, having felt the unloving bed of

dozens of women, is the person destroyed by the relationship he forges with

Noel. At the beginning, despite his experience and her virginity, he is directed towards the unhappier of Tennyson’s comparison; Noel, on the other

hand, has the romantic posture of someone destined for the lost that

remains, which may come to her after a series of loves lost. She, the

adventurer willing to accept her own pitfalls, would have been happy had she

never stepped into Paul’s life while he would have been just as blind to the

outside world without her. He’s loved and lost, and seems all to willing to

linger on this, but we know that he’s the better for it. |

|

| ©2003, David Perry, Cinema-Scene.com, 9 May 2003 | ||