Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: |

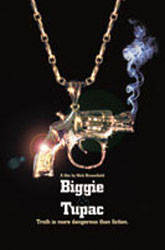

Biggie and Tupac BY: DAVID PERRY One of my favorite moments in documentary filmmaking in the past decade was when Heidi Fleiss and some local news reporter began to make fun of filmmaker Nick Broomfield because his boom mike, unlike the other reporter's, lacks a number on it. Broomfield, who is usually working for the BBC, finds it incredulous: in America, only those with a stupid channel number on their microphone get respect. The film he was working on was the infamous Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam, the second Broomfield film to get a major release in America (following Fetishes) and the only one to really make a mark with critics and art house audiences. It was also manipulative, deceiving, and ranting -- all of which turns it into one of the most entertaining documentaries to come out in years. His last two major efforts come from deaths, meaning that they should not bring the same level of enjoyment. Nevertheless, Broomfield's charm keeps making these movies -- which have him in front of the camera more than the subjects -- as instantly humorous as Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam. Heidi Fleiss came from the same mold of Broomfield's previous films: simple roving camera documentaries that try to understand the oddities in people's lives or the lives of odd people. Heidi Fleiss (and later Margaret Thatcher) made for a perfect subject. These later two films take a different form, a type of muckraking encapsulation of '90s celebrity and tabloid journalism. It's seems fitting that Broomfield bares a slight resemblance to Oliver Stone. The first of these two was Kurt and Courtney, an underrated gem that attempted (unconvincingly) to show that Courtney Love might have had Kurt Cobain murdered. While most of the people Broomfield's interviews seems to have been found under some rock (especially the unforgettable Il Duce), there is a constant among them in Broomfield. He serves as the Puck of these stories, standing alongside trying to find sense in all the commotion surrounding him. Biggie and Tupac is similar in that it follows conspiracy theories surrounding a famous musical death. In this case, it is the 13 September 1996 killing of Tupac Shakur in Las Vegas and the 9 March 1997 killing of Christopher "The Notorious B.I.G." Smalls in Los Angeles. Since 1996, it has been rumored that Smalls had something to do with Shakur's death and that his own death was in retaliation for his paid hit. A 6 September 2002 L.A. Times article went along with this idea, arguing that Smalls paid Compton Crips gang member Orlando Anderson (who, himself, was shot and killed in 1998) to kill Shakur. All this falls into place similarly in Broomfield's film, even if he comes up with a different answer. Instead, relying on the theories of former L.A.P.D. cop Russell Poole, Broomfield believes that Marion "Suge" Knight, impresario of Death Row Records and landlord of the Shakur discography, killed Shakur when the rapper decided to leave Death Row Records due to mounting payment failures by Knight. Smalls was then killed by Knight to make it seem that there was some West Coast (embodied by Knight and Shakur) and East Coast (embodied by Smalls and Bad Boy Records owner Sean "Puff Daddy" Combs) rivalry at work. None of this ever becomes immensely convincing, but it all remains interesting. Broomfield becomes entranced by the so-called revelations he's privy to that it becomes more fun to watch him rally around the interviewees like they are giving vital information even if it seems like pure lies and embellishments. Amidst all this, the most surprising moments of the film do not come in any of Broomfield's great interviews with Poole or Knight, but in learning facts like Smalls' upper-middle-class upbringing, even attending private school. His mother (who comes as a reminder of the upright peripheral characters touched by the crimes in the violent hip-hop community) remembers her embarrassment when her son did a song about not having enough to eat for dinner and living in a cramped house. She understands that this is a persona that he needed to use to sell records, but it still hurts to hear her son comment on having the upbringing she worked to keep him from living. All the while, it is the perseverance of Nick Broomfield

that turns Biggie and Tupac into much more than an America Undercover

special. He comes in and out of the stories he follows with gumption and confidence. In

many occasions, he's putting his life on the line (he seems to run every red light in

L.A., as well as received 10 to 15 death threats each day while making this film) but

keeps pushing harder into the violent stories he has become obsessed with. At one point,

he's thrown out of an office and just stubbornly keeps standing there and discouragedly

watches as his cameraman starts to leave the place; in the film's climactic trip to Suge

Knight's prison, his cameraman is replaced because she dropped out for "self

preservation." All the while, that impish little Brit with the headphones and boom

mike still stands there in front of the camera. |