|

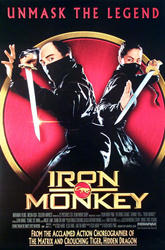

Iron Monkey

(Dir: Yuen Wo-Ping, Starring Donnie Yen, Yu Rong-Guang, Tsang Sze-Man, Jean Wang, Yuen Shun-Yee, James Wong, Yan Yee Kwan, Yam Sai-kun, and Li Fai) BY: DAVID PERRY |

| Cinema-Scene.com > Volume 3 > Number 42 |

Cinema-Scene.com

Volume 3, Number 42

This Week's Reviews: Iron Monkey, Mulholland Dr., Corky Romano, The Last Castle, From Hell, K-Pax.

This Week's Omissions: Liam, Riding in Cars with Boys.

|

Iron Monkey

(Dir: Yuen Wo-Ping, Starring Donnie Yen, Yu Rong-Guang, Tsang Sze-Man, Jean Wang, Yuen Shun-Yee, James Wong, Yan Yee Kwan, Yam Sai-kun, and Li Fai) BY: DAVID PERRY |

In 1993, Yuen Wo-Ping directed the film Iron Monkey, a Hong Kong action film that would stand as one of the genre's biggest successes. However, the film never played in American theatres over the last eight years -- distributors have never held confidence in American audiences to open up to the cultural change in action films. But that was then: Wo-Ping is now a highly sought man in the film world, fresh off of his stunt choreography for The Matrix and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Now, thanks to Miramax believing in Americans and the always zealous adoration of Quentin Tarantino, Iron Monkey falls into theatres.

Not much has changed from the original, which has been available in US video stores for years. Besides some a new score (which was highly needed off of the original's horrible synthesizer music), a couple edits to take out the slapstick comedy, and subtitles, Iron Monkey comes to theatres in the same form as has enthralled millions of fans in the past.

The film follows the exploits of a young Wong Fei-Hung. This name probably does not ring many bells for most people, but in China the Wong Fei-Hung name is synonymous with a long and loved legend. Many people have probably run into the stories before, just not knowing it. Films like Once Upon a Time in China and The Legend of Drunken Master have come from the adult exploits of Wong Fei-Hung. In past movies, big names like Jet Li and Jackie Chan have played the role.

Wong and his father Wong Kei-Ying (Yen) appear in the film as a visit south to a small Chinese village. In this town, a Robin Hood figure has enraged the police and government while earning the support of the poor. This humanitarian calls himself Iron Monkey, but in reality he is Dr. Yang (Yu). He, with his Kato-like adopted daughter and nurse Miss Orchid (Wang), breaks into the homes of the rich, especially the town's gluttonous governor, and then proceeds to drop bags of gold around the slums afterwards.

Governor Cheng (Wong) learns that a royal administrator is coming to inspect the town and decide whether or not to replace Cheng. He knows that Iron Monkey will not refrain from attacking when the inspector is in town, so he ups the search for the hero. When his bumbling police captain (Yuen, the director's younger brother) rounds up two dozen suspects (most of whom were chosen only because they had a sign referring to monkeys or has a pet monkey) including the visiting Wong family. Iron Monkey comes in to save the day, but master fighter Wong Kei-Ying proves his abilities in front of the governor at the time and inadvertently opens himself to an ultimatum: if Wong will capture Iron Monkey, the governor will let his son go.

Of course, soon Wong learns that this Iron Monkey is actually a good guy, and unknowingly turns out living in the Yang household for a time. He has seven days to save his son, and even after that, the inspector will be in town.

The story really does not matter with Iron Monkey -- almost every person going to see the film will only care about the action. Yes, the action is often thrilling, but at the same time obligatory. The lyrical, balletic beauty of the some scenes feel force fed because they are expected. Perhaps I have been spoiled by Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, but the action in this film really does not feel as important to the experience.

And that's a huge problem. When the film's only asset is the action and even it is not absolutely commanding, then its time to start rethinking things. I commend Yuen Wo-Ping for the effort, but not for the product. The drama, comedy, and dialogue are almost painful to sit through, and the legend, which probably works better for those completely knowledgeable of its extent, does not really help the film to save face.

I could make countless references to justify my feelings

comparing Iron Monkey to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, but that would

be unfair -- Crouching Tiger was so tightly put together with its story that the

action seemed like a momentary (and awe inspiring) distraction from the main narrative.

What's easier to compare the film to is Time and Tide, which I reviewed earlier

this year when it came to America. That film, not surprisingly, has a connection to Iron

Monkey through prolific Chinese director Tsui Hark (he directed Time and Tide,

produced Iron Monkey). Both movies were action-packed excursions with little

emphasis on the story. But I liked Time and Tide more because I could feel the

confidence from the director that he was more than willing to show his action expertise

without pushing the plot. Sure, Yuen Wo-Ping knows what he's doing but it doesn't come to

life in Iron Monkey. Instead I'll just turn to his cooperative with Ang Lee.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

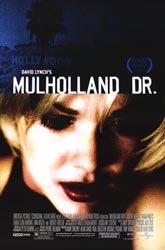

Mulholland Dr. (Dir: David Lynch, Starring Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, Justin Theroux, Ann Miller, Michael J. Anderson, Scott Coffey, Melissa George, Monty Montgomery, Katherine Towne, Elizabeth Lackey, James Karen, Lee Grant, Chad Everett, Diane Baker, Robert Forster, and Angelo Badalamenti) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Trying to understand a David Lynch film is like trying to read a novel in a foreign language -- the devices may be incredible to encounter but completely ambiguous. I respect him as a filmmaker; his movies are always worth seeing even if they occasionally get too surreal for their own good. That happened with Lynch's last attempt at Dadaism, Lost Highway, and he chose to rebound using a complete departure from his style with The Straight Story.

Mulholland Dr. is the return to the old Lynch, the man with an eye for the unimaginable. He is the quintessential voyeur of cinema, and Mulholland Dr. is his finest visualization of the licentious. I'm willing to say that Mulholland Dr. is Lynch's best film.

The film, of course, would never have come to light in this version had the execs over at ABC seen the wonderland David Lynch imagined with the Mulholland Dr. series he wanted to create. The first 100 minutes or so of the movie once served as the pilot episode for Lynch's follow-up series to Twin Peaks. Having sit through the end product, I cannot decide whether I should thank ABC or not. Without a doubt, a series would have allowed a longer state to see Lynch's vision, but, alternately, the end product would probably have been a different creation altogether.

A quagmire of visual splendor and repulsion, Mulholland Dr. is one of those films that continues to haunt you for hours, perhaps days, after viewing. It is the Lynchian nightmare and dreamscape that go beyond mere words to discuss. A post show conversation comes down to a collection of inexact utterances attempting to piece coherent thought. Lynch is so remarkable in playing with the audience (in this occasion, his most-willing marionettes) that we have trouble immediately continuing life once he lets go of the strings.

The plot behind Mulholland Dr. is tough to impart in a review -- Lynch has so crafted his story one could understandably make the argument that no one scene (sans one in a club called El Club Silencio) is the complete embodiment of what the movie is about. I could write a ranting 600 words on the storyline and yet have told you absolutely nothing about the film. If you want some form of an outline, I'll be kind and oblige, but take heed that nothing is truly as it may seem:

The movie opens in the eyes of a naïve young lady coming from her Ontario home to Hollywood with dreams of becoming an actress. Lynch immediately sets the mood within seconds of her arrival: the kind old couple she sat with on the plane get in their ride from the airport and laugh uncontrollably at Betty (Watts), the perfectly named ingénue.

Betty's aunt, a somewhat successful actress, has given her terrace apartment to Betty while she goes abroad for a film shoot. But all is not well in the residence -- the previous night a lost woman wandered into the home after a car wreck. She calls herself Rita (Harring), a name chosen because of a Rita Hayworth poster on the wall since she has no memory of her life prior to the crash. Betty takes Rita in as a friend and confidante, her only real acquaintance in the city. By the down-home intrigue this evokes for Betty, she is soon drawn to Rita's plight and begins the hunt to figure out who Rita once was.

Meanwhile, a young filmmaker finds his career is not his pronouncement. Adam Kesher (Theroux) is devout to his decisions, but soon finds that Hollywood is a machine unwilling to bend for a new engineer. Early in the film, he is eaten by the system -- his choice in the lead actress for his new film is completely out of his hands, all the real choices are made by a mysterious dwarf living in a glass room (the man, and the red art design of the room, should bring instant memories for fans of Twin Peaks).

Lynch's wonderland is something of a kaleidoscope -- one of film genres, one of storytelling techniques, one of unconscious splendor. He crafts the movie out of tools unlike most directors and creates a film that embodies his entire filmography. A mysterious cowboy brings memories of Lost Highway's Robert Blake character; a strong lustiness between characters hearkens back to Wild at Heart; and the Betty and Rita characters seem almost like later variations on Blue Velvet's Sandy Williams and Dorothy Vallens. Lynch's web of mystery is strong partly because it is established already. Anyone entering the film without prior knowledge of the Lynch oeuvre will be quickly lost in his illusions.

The director's normal troupe of artisans create seamless designs to help Lynch with his toys. Patricia Norris' sets are like expressionist realizations of the most surreal (looking at Betty's interim home, sometimes the most normal surroundings seem the most alien in a Lynch film); Duwayne Dunham's editing keeps the film flowing briskly through the visual rhetoric despite a two hour length; Frederick Elmes' cinematography captures the lush colors and dark fissures in the cinematic palette; and Angelo Badalamenti's score reveals the unraveled eeriness in the film's most conjugal moments.

Watching Mulholland Dr. brings memories of so many other films, some of which may have been intentional by Lynch, others completely coincidental. The touches of Vertigo, not to mention the Hitchcockian look of the two female leads, remains strong in the film's middle section; the surrealism and innermost lustfulness feels like a child of Buñuel, especially in Belle de Jour; and the relationship between these two characters, besides the aforementioned Blue Velvet connection, seem like Lynch's fusion of his Blue Velvet characters with Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann in Bergman's Persona.

I wrote earlier of a scene at the El Club Silencio -- that scene, to me at least, serves as everything that is awe-inspiring about Mulholland Dr. Every frame emits the perfection of a fine artist. This place, where the film turns to the surrealist side Lynch is best known for, can be easily taken as a chance for the characters to change. But I counter: this scene is the one that changes the audience. The people sitting in the seats of a comfy theatre have lost their comfort. Where the film was quizzical before this scene, it is now unpleasant. The audience is merely left to put together the pieces.

That reminds me of an observation I made once of Lynch's

films: if you think you know everything there is to know, you probably know nothing.

Putting together the pieces of Mulholland Dr. after watching the movie is a

futile task. This film is the crazy yet enthralling vision of a true auteur -- a man who

has made his bed, slept in it, and shared all his nightmares for the world.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

Corky Romano

(Dir: Rob Pritts, Starring Chris Kattan, Peter Berg, Chris Penn, Vinessa Shaw, Matthew Glave, Peter Falk, Fred Ward, Richard Roundtree, Dave Sheridan, James Tupper, Rena Mero, Martin Klebba, Jennifer Gimenez, Roger Fan, and Vincent Pastore) BY: DAVID PERRY |

The Mafia has been a favorite subject in films over the years -- as far back as Public Enemy, audiences have frolicked to stories of gangsters and their brethren. Last week, Paramount was kind enough to release on DVD the finest titles in the subgenre, Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather trilogy. In fact, as I write this, the first film is playing as Luca Brazzi's message is sent to Sonny. Why, you may ask, is this important in a review subjected to be on Corky Romano? Well, in all actuality, I'm just happy to not have to think about that film for moment.

There is a Mafia plotline in Corky Romano, but it's so forgettable by the end of the film's opening titles that any neo-consigliore feels like a fly on the board. This film, sadly a late in the year release by Touchstone merely weeks from the same slot when they unveiled The Insider two years ago, has to be one of the most painfully unfunny movies to come out of the woodworks this year. No, it's not as incomprehensible as Pootie Tang, or as abrasive as Freddy Got Fingered, but Corky Romano does deserve some heavy panning. It might not be offending to watch, but it does commit the fatal crime for a comedy: it's not funny.

Chris Kattan's work on Saturday Night Live has occasionally brought some laughs, but he's definitely one of the troupe's least even performers. Kattan, like Night at the Roxbury's costar Will Farrell, hasn't the comedic abilities to stand on his own for laughs, but instead must turn to unusual characterizations (Farrell, I might add, has only been funny when playing Alex Trebek and George W. Bush). Give me Tina Fey any day.

Adam Sandler has perhaps stood as the biggest success stories to come from the latter-day SNL members. His early films were so critically maligned that it seemed he would never rise above the aggressive loud mouth that made films like Billy Madison and Happy Gilmore so painful. But, alas, those films created a huge career for Sandler, and Kattan, with all his might, is trying to recreate that star-making performance.

Kattan's Corky Romano seems like a kind and gentle version of Sandler's Billy Madison. Both are small children trapped in adult bodies, sometimes too small for all the energy they need to discharge. They are sons eclipsed by their unloving fathers, they are tools of the legal system, and, most importantly, they are tedious characters to watch for 90 minutes. The Romano character is definitely more likable, but at the same time is less interesting to watch. Madison was no paean of entertainment, but at least he seemed ready to move beyond the ridiculous aspirations of the movie (a touch that I think Sandler made work in Big Daddy).

Peter Berg and Chris Penn have the poor luck of playing whipping boys in the film -- their aggressors are meant as figures to dislike for the sake of later gratification. In a weird way, I'd come close to stating they are the Bluto figures of the film (yes, I'm actually going to refer to Popeye in a review -- a far cry from my normal Molière and Nietzsche) in that they are maligned only because they are able to get what they want. With that, it becomes rather hard to figure any way the film can deal with the characters other than the obvious.

What's worse, though, is seeing Peter Falk cruising his way through yet another painful role. The actor has been in some of the finest films ever made, not to mention his tenure as Lt. Colombo. His comedy credits are rather notable too -- Murder by Death, The Cheap Detective, The Princess Bride -- but all is almost forgotten for today's generation, whose only knowledge of the actor is in films like Corky Romano and Made playing essentially the same character in both.

Corky Romano has little to speak of that is

worthwhile, and yet I'm not giving it my lowest rating. The film deserves no respect, but

I cannot completely run against it after sitting through some worse comedies this year.

Call it a D by comparison, not by quality. Thankfully, my mind will forget Corky

Romano when the second season box set of The Sopranos comes out soon.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

The Last Castle (Dir: Rod Lurie, Starring Robert Redford, James Gandolfini, Mark Ruffalo, Clifton Collins, Jr., Steve Burton, Nick Kokich, Delroy Lindo, Mike Irby, Matt Mangum, Dean Hall, Brian Goodman, Sean Cameron, Jeremy Childs, Maurice Bullard, Robin Wright Penn, and David Alford) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Lieutenant Maréchal and Captain von Rauffenstein in Grand Illusion, Colonel Nicholson and Colonel Saito in The Bridge on the River Kwai, Captain Hilts and Colonel Von Luger in The Great Escape, Sifton and Colonel Von Scherbach in Stalag 17 -- films have a long history of feuds between soldiers in prison. However, before The Last Castle, I cannot think of any film about a prison court-martial leading to the clashing of two military minds (well, with the exception of A Few Good Men, but that never made it to a military prison).

It is somewhat new in that respect, but Rod Lurie's exercise in flag-waving lacks anything new beyond it. The critic-turned-director has surely seen all those films plus Cool Hand Luke and The Shawshank Redemption and pined over eliciting his emotions on the screen to represent the feelings he has from a West Point background. I respect him for trying to pull the auteur deal and that he is following the footsteps of names like Bogdanovich, Truffaut, and Godard -- I'm just constantly disturbed that his creations are never too notable.

Deterrence, about a president wrestling over nuclear threats and collateral damage, and The Contender, about the overzealous tabloid obsession over political figures, bore interesting ideas with little follow-through. Lurie's tenure as a critic would make me think he'd be the first person to steer clear of cliché and formula, but his films, especially The Last Castle, feel like the one-sided musings of a man running a computer generated screenplay machine. I have nothing against a film with deep beliefs, but when the beliefs are so overdone that the pleasure of watching the film is hindered by it, then I get a little perturbed.

The Last Castle yearns to be worthy of comparison to all those films I wrote about earlier -- the audience feels Lurie's probable love for the films and intent on making his own realization of their stories. A sort-of homage that becomes unbearable is the easiest way to describe Lurie's solicitous film. It may have some high points in the later scenes, but the early ones are hard to watch.

The dueling minds in this prison are those of General Irwin (Redford) and Colonel Winter (Gandolfini). Irwin made a miscalculation on the field and has been court-martialed and sent to the prison run with an iron fist by Winter. Irwin is a highly decorated, highly regarded officer with experience in the Gulf and the Balkans; Winter is weak but powerful, never fighting in the field, but constantly using his aggressive training on the prisoners. When Irwin arrives at the prison, Winter states "they should be naming a base after the man instead of sending him here."

Winter is willing to make Irwin's stay an easy one, but something early on -- when the general is overheard criticizing the colonel's military artifact collection: "Any man with a collection like this has never set foot on a battlefield" -- makes Winter rethink any leverage for his hero. Immediately Winter, a person in awe of Irwin, is brought to anger -- he is just as enraged by the overshadowing of a believed underling as the composer of the symphonies he listens to in his office: Antonio Salieri.

While Winter tightens the command over the compound, Irwin begins creating his own army out of the fellow inmates. Nearly every man in the place starts saluting their commanding officer and further enraging the man they are supposed to salute. The only person not quite buying into Irwin's authority is the prison's gambling bookie, Yates (Ruffalo), whose father served under Irwin at a POW camp in Hanoi.

The two lead actors seem secure in their characterizations and should receive some credit. Redford, the miraculously worn former teen idol, gives an exasperating physical personification of Irwin. Someone remarked that a change in lead might have helped the film -- I disagree, it is the choice of Redford for the character that actually saves the film from complete failure.

Gandolfini has chosen some interesting roles over the years, and this actually seems like the first completely passive authoritarian in the bunch. This is a far cry from Tony Soprano -- Winter is a weakling in a giant's body. Gandolfini lends the role a great deal of humility that might have been lost on other actors. I especially liked the way he seems ready to curl into a fetal position whenever things do not go his way.

But fine actors cannot save the dialogue by David Scarpa and Graham Yost, which veers in directions that Akiva Goldsman might honor. Yeah, the Salieri reference works, but the film is filled with a compendium of metaphors throughout that become redundant as the movie progresses. Despite the work of James Gandolfini, the screenplay makes him into a one-sided bad guy much like the maltreatment of Gary Oldman's republican senator in Lurie's deeply liberal The Contender. Lurie lacks the prowess to cut back on the exhibition and allow the actors to work their magic.

The screenplay is not the only work where Lurie needed to use some conservatism (though, based on the politics of his previous films, I'd imagine he'd fear acting conservative in any way); he also overuses some of the most appealing cinematic toys. I happen to be a huge fan of filmmaker using deep focus to create the needed ambiance of a scene -- Dante Spinotti, in films ranging from Wonder Boys to The Insider, has given the technique its best use -- but Lurie overuses it. The first couple times I was quite happy that he went with the method, but once he and cinematographer Shelly Johnson try deep focus for the tenth time it's become old hat.

The film does reach a high point in the last thirty

minutes, as mutiny begins to arise, but, in great Lurie fashion, the actual ending helps

to negate all the impact of the preceding scenes. Like Deterrence and The

Contender, The Last Castle is filled with many great touches, but the

completed productions is, in the end, lacking.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

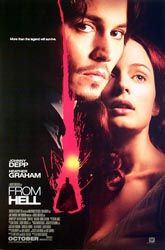

From Hell

(Dir: Allen and Albert Hughes, Starring Johnny Depp, Heather Graham, Robbie Coltrane, Bryon Fear, Paul Rhys, Joanna Page, Katrin Cartlidge, Annabelle Apsion, Susan Lynch, Sophia Myles, Lesley Sharp, Stephen Milton, Ian Richardson, Ian McNeice, and Jason Flemyng) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Hundreds of serial killers have come out of the woodworks since 1888, and yet none have eclipsed Jack the Ripper in fame. Most any high profile serial killer has killed more than Jack did (believed to be seven or nine women, depending upon the source), and still no one can compare in name recognition. The key, perhaps, is that Jack was never caught -- now, 113 years later, his identity is still a mystery. That is why he remains the interest of so many true crime novels and short stories. Nearly everyone has a theory on Jack the Ripper (one of my favorites, though completely absurd, is found in a novella called Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper) and this has made for a century of movies, plays, and novels celebrating his divine anonymity.

Now comes From Hell, a variation on Jack's murders, by filmmakers Allen and Albert Hughes. The brothers are best known for their self-proclaimed "ghetto films," and have already said that their new film follows in line with the others, just that it is now a white ghetto. The ghetto in question is the East End section of London, where Jack chose his victims. The ladies, all prostitutes, were taken off the streets, had their throats cut, and were then relieved of one of their body parts. A picture I saw in high school still remains with me: a lady laying in bed with her breasts cut off and one sitting in the table beside her.

Jack towered over his reign of terror -- lasting less than a year -- as proudly as Robespierre dwelled over his Reign nearly a century earlier. He taunted the authorities with letters signed "From Hell, Jack the Ripper" and continued to commit these crimes right under their watching eyes. The film From Hell is mainly through the eyes of one inspector, Frederick Abberline (Depp), who believes he sees Jack's murders before they happen after he smokes opium and drinks absinthe. He is hated by the police establishment because his seemingly idiotic techniques often lead to truth -- the only person who has any respect for him is his partner Peter Godley (Coltrane).

According to this film, all the young ladies murdered were good friends. In fact, at times, they are live together during the day before they go out to work in the night. The main interest of the sorority of prostitutes is Mary Kelly (Graham), an Irish immigrant intent on making enough money to go back home. She befriends Inspector Abberline as he investigates the murders of her friends -- soon it becomes apparent that they have feelings for each other.

The romance subplot in From Hell is just one of the film's many misgivings, few of which come from a 500-page graphic novel by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell. That novel, which is best known for its intense obsession with detail (I have not read it, but I have heard that it has some 40 pages of footnotes in tiny print), serves the film much like Daniel Clowes' Ghost World did for the film of the same name. In graphic novels, artists can create their stories in visual harmony with their feelings. Much like animated films, Ghost World and From Hell use their often surreal visual touches to create disharmony in their subjects.

The Hughes brothers are talented enough to shape their visions of the story onto the screen through the graphic novel. Their images (with a great deal of help from cinematographer Peter Deming, fresh off of Mulholland Dr.) enact a somewhat predatory style to their camerawork that successfully grasps the savagery of the film's historical predator. The strongest asset in the film is the photography, which goes far beyond the restraints of the story.

The screenplay by Terry Hayes and Rafael Yglesias rarely captures the strengths of the history. The characters seem so caught up in unimportant details (like lobotomy and the royal family) that when the details become important to the story, the audience is rather tired of hearing about them. Johnny Depp played similar investigators in The Ninth Gate and Sleepy Hollow, but those characters had far more interesting concerns.

From Hell keeps the story of Jack the Ripper running pretty

well -- though the excessive length of the movie is felt in the middle and closing moments

-- and it never takes too long for the movie to become crimson and gory for those

searching some semblance of horror in the film. But everything feels resistant in

retrospect. The filmmakers have, unfortunately, created a movie about Jack the Ripper with

as many holes as the actual mystery behind the man.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

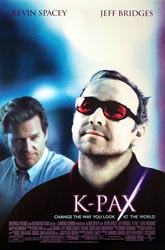

K-Pax

(Dir: Iain Softley, Starring Kevin Spacey, Jeff Bridges, Brian Howe, Alfre Woodard, Ajay Naidu, Mary McCormack, Kimberly Scott, Conchata Ferrell, Saul Williams, David Patrick Kelly, Melanee Murray, Tracey Vilar, Celia Weston, Peter Gerety, and Vincent Laresca) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Jack Kerouac once wrote, "All life is a foreign country." Some years later, as the beatnik years were coming to a close, Robert A. Heinlein wrote Stranger in a Strange Land about a Mars-born human coming to Earth and questioning modern lifestyles. Both of these men did ten times more for the ideas of being lost in a foreign world than Iain Softley does with his K-Pax. Does he have aspirations for the levels touched by his predecessors? Probably not, but that does not excuse him for making a sloppy little film.

K-Pax, similarly to Stranger in a Strange Land (though, in truth, it is adapted from a Gene Brewer novel and, albeit not credited, a Spanish film called Man Facing Southeast), is about an extraterrestrial dealing with the human experience. The hitch this time, however, is that the alien's credibility is in question -- no one really believes he is from a planet and galaxy far away.

He calls himself Prot (Spacey), living in a body that is effectively engineered -- in other words, he looks like an everyday human. When he comes out to save a woman from a purse snatching, Prot is questioned by police and deemed insane due to his rantings of an otherworldly home called K-Pax. He is sent to the Psychiatric Institute of Manhattan, where Dr. Mark Powell (Bridges) is given his case. Skepticism is immediate, but soon even Dr. Powell joins the inmates in believing Prot may actually be from another planet.

A great deal of effort is made by Iain Softley and screenwriter Charles Leavitt to convince the audience that -- plausibility not withstanding -- Prot is the alien he professes to be. When the two work in this arena, the film is watchable. Sure, there are many bumpy areas, especially in a slapdash subplot dealing with Powell's rocky marriage, but the first two acts of the film are acceptable as a good movie. It's in the third act -- where the screenwriter's work on The Sunchaser comes to light -- that the movie crashes to a halt.

Softley and cinematographer John Mathieson (Gladiator) create some fine images throughout the film. If there's something to speak of that remains consistently remarkable, it's the imagery. Sure, things get a little heavy-handed (if the movie had made one more reference to bubbles...) but all is forgiven as they continue working imaginative shots.

The two lead actors try their best to create enough emotion in the doctor-patient relationship, and they each come out fine. This is not another Pay It Forward for Spacey, who is still getting some (somewhat appropriate) criticisms for that sap-on-a-stick Mimi Leder film, but it is in close ballpark. To say he comes out of the film unscathed would be untrue, but he does allow the film, through his fine performance, to have a consistent amount of respectability running through its hokum.

If this was a better film -- and it did have a great deal of potential considering the early scenes -- the damning third act would not be as painful to watch. Many films have lost their steam in the continuation of the events, but few lose it so considerably. The audience remains interested with the dynamics of the central mystery despite a horrendous visit by Prot to Powell's home and the overwhelmingly painful characterizations of the other insane patients (had the cast needed two more characters, they would have definitely thrown in a person with a Napoleonic complex). However, after a long 25 minutes of this with very little innovation, the movie becomes just as uninteresting as those patients' fears. So what if a guy is afraid to eat foods with bones? So what if Prot can draw his solar system in the New York planetarium?

My grievances are, perhaps, trite, but they are definitely

present in my mind. If there had been anything running in the mind of the filmmakers other

than saccharine and visions of wet handkerchiefs, then I might be a little more tolerant.

As it is, though, I can only sit in wonderment at such a huge waste of talents.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

Reviews by:

David Perry

©2001, Cinema-Scene.com

http://www.cinema-scene.com